Di Cavalcanti

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1897 —

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 1976

The sensitivity with which Di Cavalcanti elaborated in his work the innovations of modernism comes proportionally from the intimacy with which he invested his plastic strength in what is fleeting and impure in life. In constant company of a cast of characters, to whom he gave archetypal status, Di Cavalcanti opened the path of our first modernism with works that recreate figuration by the invention of national imagery.

Since the beginning of his production, the artist from Rio de Janeiro showed interest in themes of the urban social context of Rio de Janeiro, as in the works Figura (1920) and Amigos [Boêmio] (1921). At the beginning of the 1920s, Di Cavalcanti played a decisive role in bringing together the modernist group from São Paulo and in organizing and publicizing the Modern Art Week of 1922, an event that is considered a fundamental milestone in the renewal of the arts in Brazil. In addition to participation as an exhibitor, Di Cavalcanti is credited with the same proposal of the week, as well as the production of the emblematic disclosure brochure.

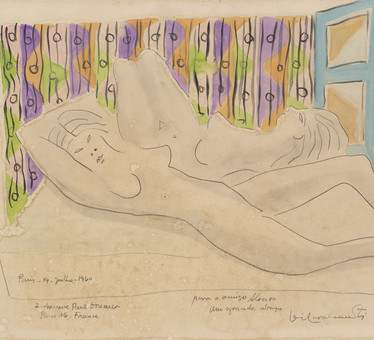

However, it is from the trip he made to Paris, in 1923, that works that characterize the singularities of Di Cavalcanti’s work began to emerge. The stay in the French capital gave Di a mission to build a new national imagery, to elaborate the modern representation of Brazilian civilization. Recalling this period, the artist reports that immersion in the Parisian cultural effervescence “transformed my love of life into love of everything that is civilized. And as a civilized person, I started to know my land ”. This love for the civilized turns to the national as a land open to a new meaning.

In 1925, the Samba canvas emerges as a fleshy and succulent fruit of this scope: in an impressive wealth of colors and under the schematic drawing that refers to the Paris School, there are the dancers, new dithyrambic priestesses with an ecstatic look that wield not the Mediterranean laurel, but the brave rue of the beaten earth. Saluting the messengers of popular singing, the dancer in red applauds and twirls, who surrenders herself to the musical charm of the fine samba dancer; the passionate bohemian, and the barefoot drunk, already beaten, complete the spatiality of Di Cavalcanti’s altar to Brazilian culture.

The works produced throughout the 1930s reinforce the artist’s interest in the country’s social issues, as in the series of cartoons The Brazilian reality (1930), an acid opposition to Vargas’s dictatorial government. Also during this period, the color of Di Cavalcanti’s works intensifies and takes on a notable role in the compositions, as can be seen in the solar work Seresta (1930) and in Cinco moças de Guaratinguetá (1930). His work as a dedicated colorist is maintained throughout Di’s pictorial production, giving substance to the experiments with figuration in works such as Pescadores (1946), Mulher de Chapéu (1952) and O grande carnaval (1953).

Capturing a universe of ideal types, artistic experimentation in Di Cavalcanti takes place by deep and continuous involvement, by faithful and disinterested friendship with these true totems of the ideal of Brazilianness that he found at times on the screen, at his side, crossing the bohemian nights .

GGS